Tai Chi: Principles, Philosophy & Practice

What is Tai Chi?

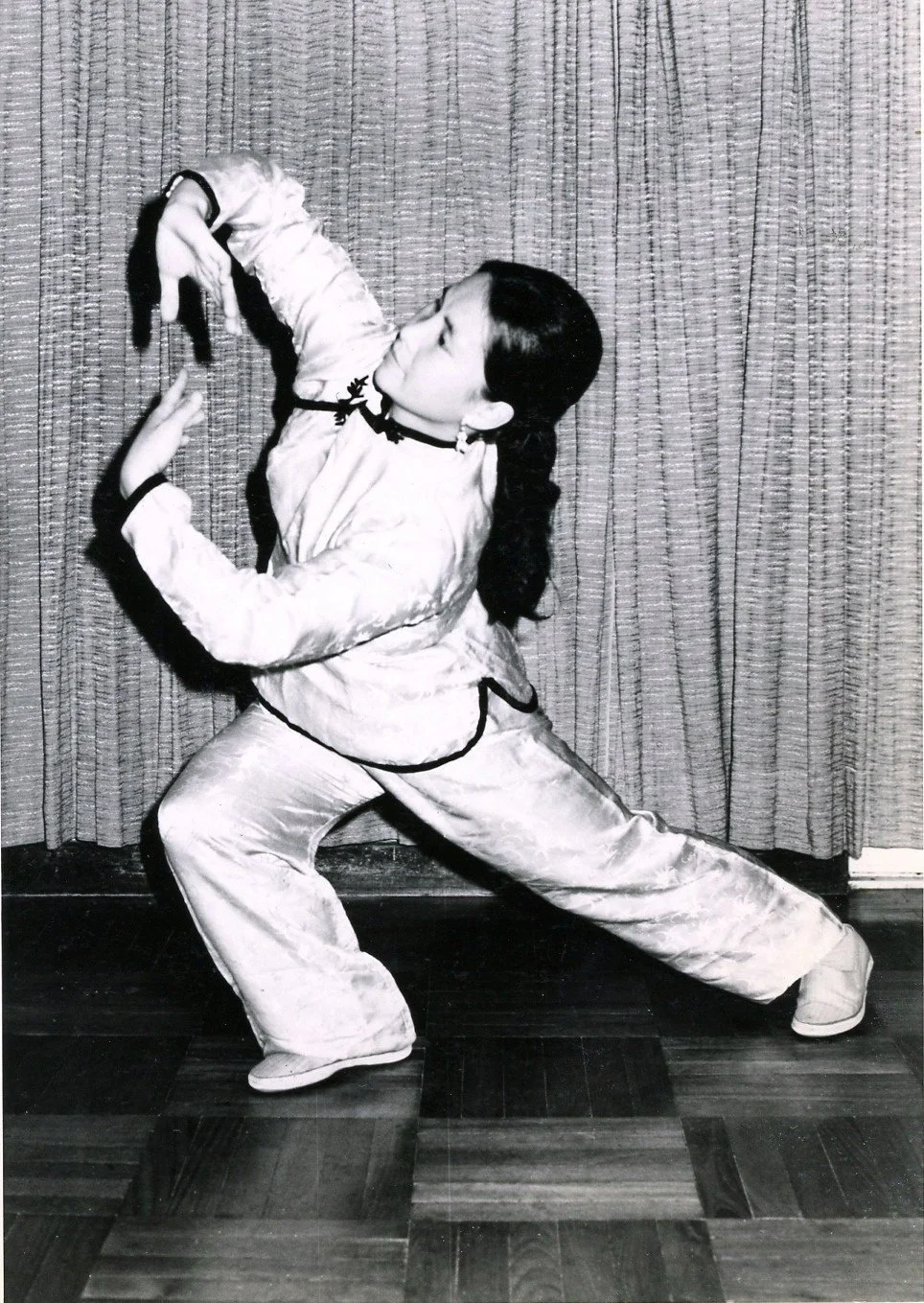

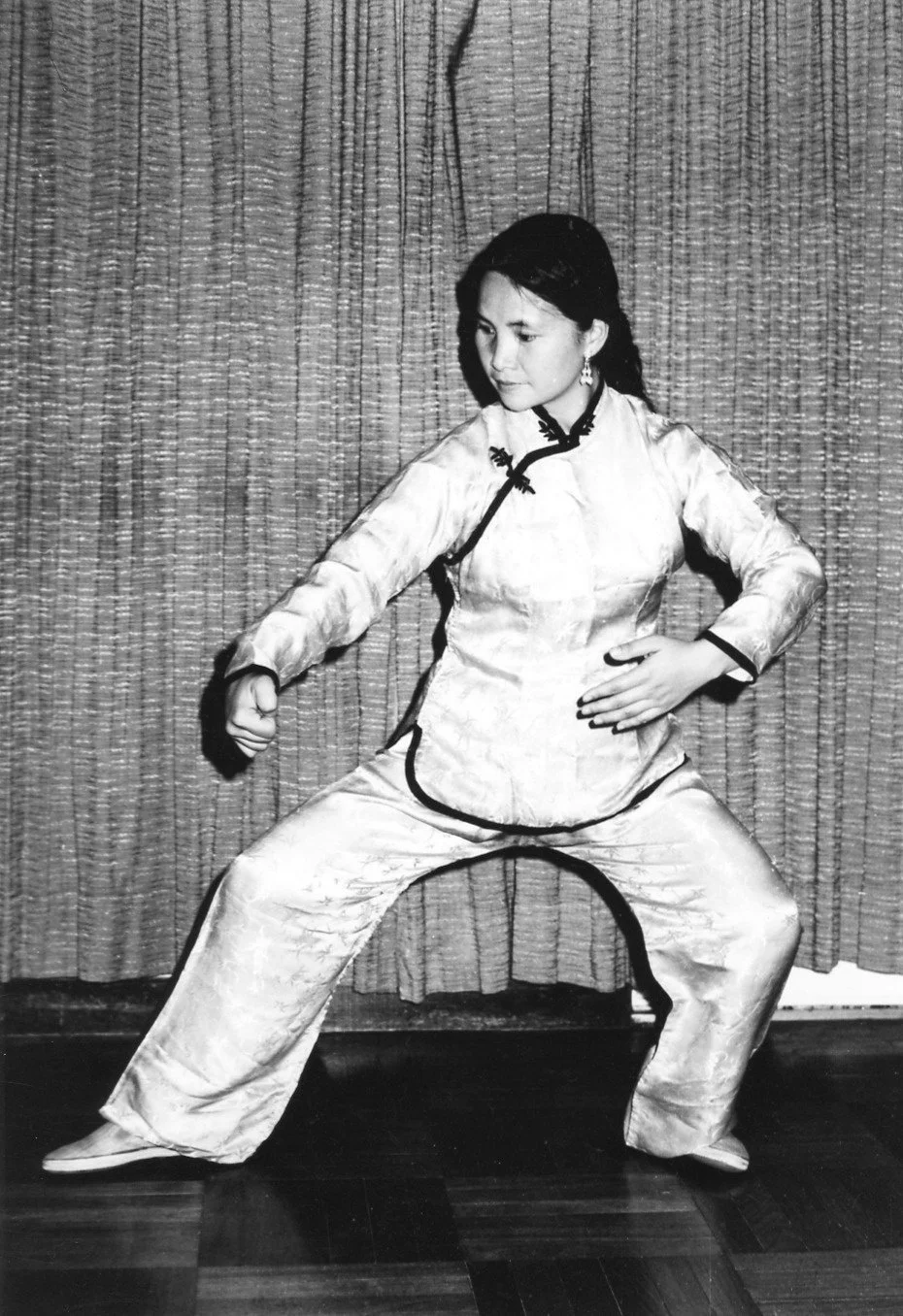

Tai Chi Chuan is an internal system of Wushu whose movements flow in circular pathways, continuously shifting between Yin and Yang. Its practice unites mind, breath, and body so the whole form moves as one piece—calm when still, whole when moving.

Master Bow Sim Mark described Tai Chi through six defining qualities:

Circularity – all actions travel on curved paths.

Relaxation – softness replaces force.

Calmness – the mind settles so the body can follow.

Continuity – movement never breaks; transitions remain seamless.

Intent – the mind guides the internal energy.

Energy – the circulation of Qi animates the limbs from within.

Her core practice requirements come directly from classical theory:

Keep Yin and Yang distinct.

Keep the lower back straight.

Sink the Qi to the Dan Tian.

Empty the chest and expand the upper back.

Sink the shoulders and elbows.

Keep the head erect.

These essentials are the foundation of her entire system.

Principles of Movement

Master Mark taught that Tai Chi is governed by specific laws of movement:

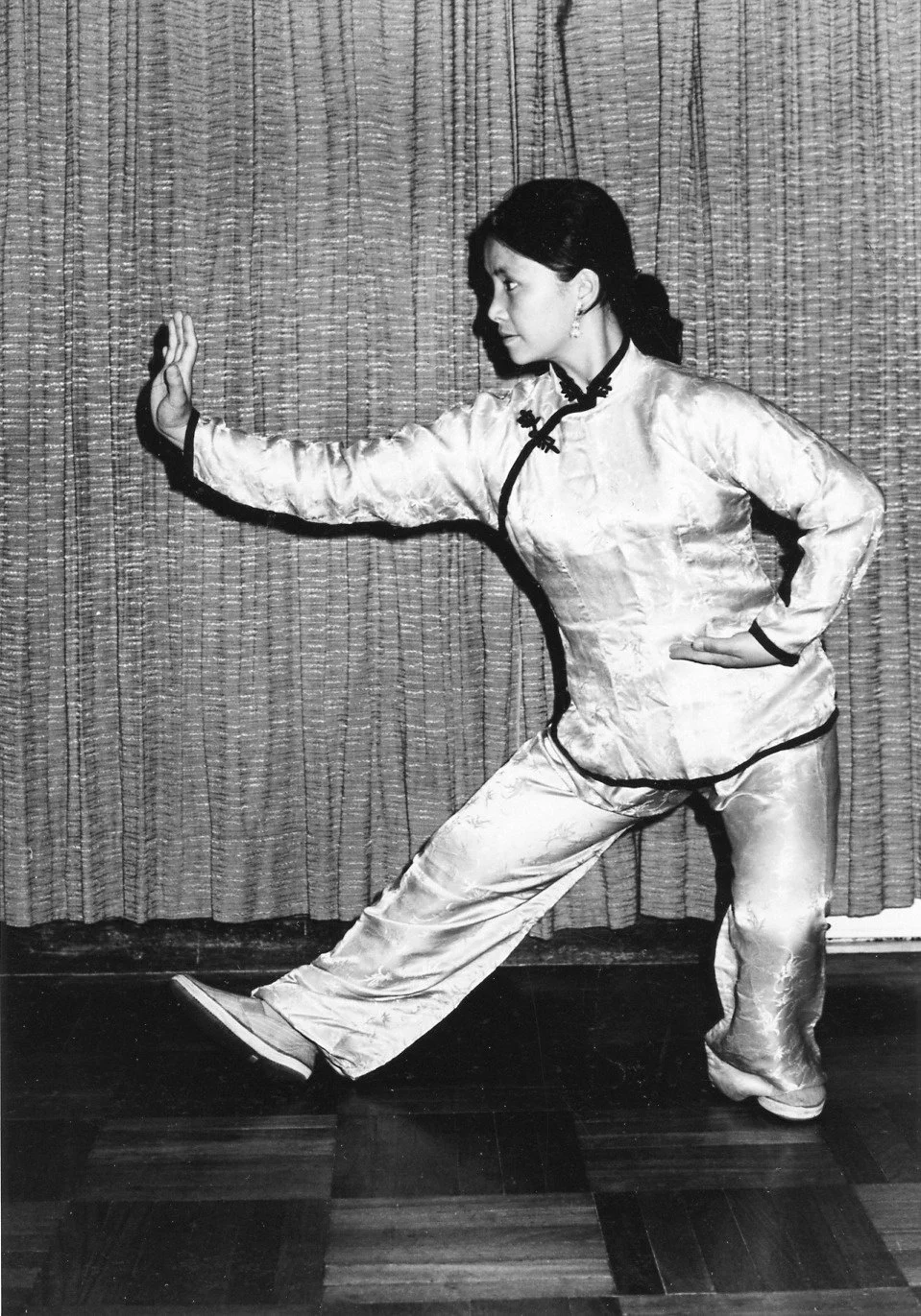

Rooted in the feet → initiated in the legs → controlled by the waist → expressed through the hands.

Every motion begins in the lower limbs, travels through the waist, and is finally shaped by the hands and fingers. This creates coordinated, whole-body movement in which no part acts alone.

Primary and secondary movement

Each posture unfolds through stages:

Primary movement – the essential action of that stage.

Secondary movement – the preparatory motion that sets up the next stage.

This progressive flow—feet → legs → waist → hands—creates Tai Chi’s rhythm and its clear distinction between Yin and Yang.

The mind moves the Qi; the Qi moves the body.

Breath, intention, and internal focus lead the circulation of Qi from the Dan Tian throughout the body. The limbs follow this internal movement rather than muscular effort.

All movements are coordinated and circular.

Upper and lower, left and right, forward and back always work in harmony. Even when a motion appears linear, its internal mechanics trace circular paths, maintaining continuity and unity across the form.

These principles define the internal logic of her Tai Chi—why it looks the way it does, and why it feels alive from within.

The Health Benefits of Tai Chi Chuan

Master Mark taught Tai Chi as both physical and internal cultivation—a practice capable of strengthening the entire body from the inside out. Though modern medicine has since confirmed many of these effects, her descriptions were remarkably ahead of their time.

Regulates the Nervous System

Deep relaxation and mental concentration calm the nervous system, helping reduce chronic tension, stress, insomnia, and mental strain.

Improves Circulation and Metabolism

Slow, soft movements paired with abdominal breathing promote efficient oxygen absorption, stimulate healthy blood flow, and support the smooth operation of the meridian system.

Massages and Conditions the Internal Organs

The opening/closing, twisting, stretching, and circular actions gently massage the liver, lungs, stomach, and digestive tract—improving harmony among the organs.

Strengthens the Skeletal Structure

Keeping the joints loose conditions the connective tissues, increases blood flow to the bones, and supports stronger bone metabolism.

Balances Hormonal Production

By regulating the glands and promoting balanced internal activity, Tai Chi supports healthier hormone levels and overall systemic harmony.

Together, these effects contribute to:

better resistance to disease

improved energy

slowed aging

and a greater sense of well-being

Master Mark often emphasized that Tai Chi is suitable for all ages and conditions—young or old, strong or weak, healthy or struggling. It requires no equipment and only a few feet of space.

She also reminded students that Tai Chi extends beyond the bare hand form: sword, broad sword, two-person sets, and push hands deepen practice and enrich understanding.